|

This article was written by Ron

Clifton for Bowling This Month Magazine and may not be copied or

reproduced without written consent from Bowling This Month. Real estate zoned for strikes

In my last article for BTM, “Breakpoints and Target Lines”, I covered the importance of having a well defined target line. The article explained how to define the target line by using two distinct points: one point at the breakpoint and one point located in the heads, usually near the arrows. To play the target line, I instructed simply drawing an imaginary line from the breakpoint back through the point you chose in the heads and bowling down that line.

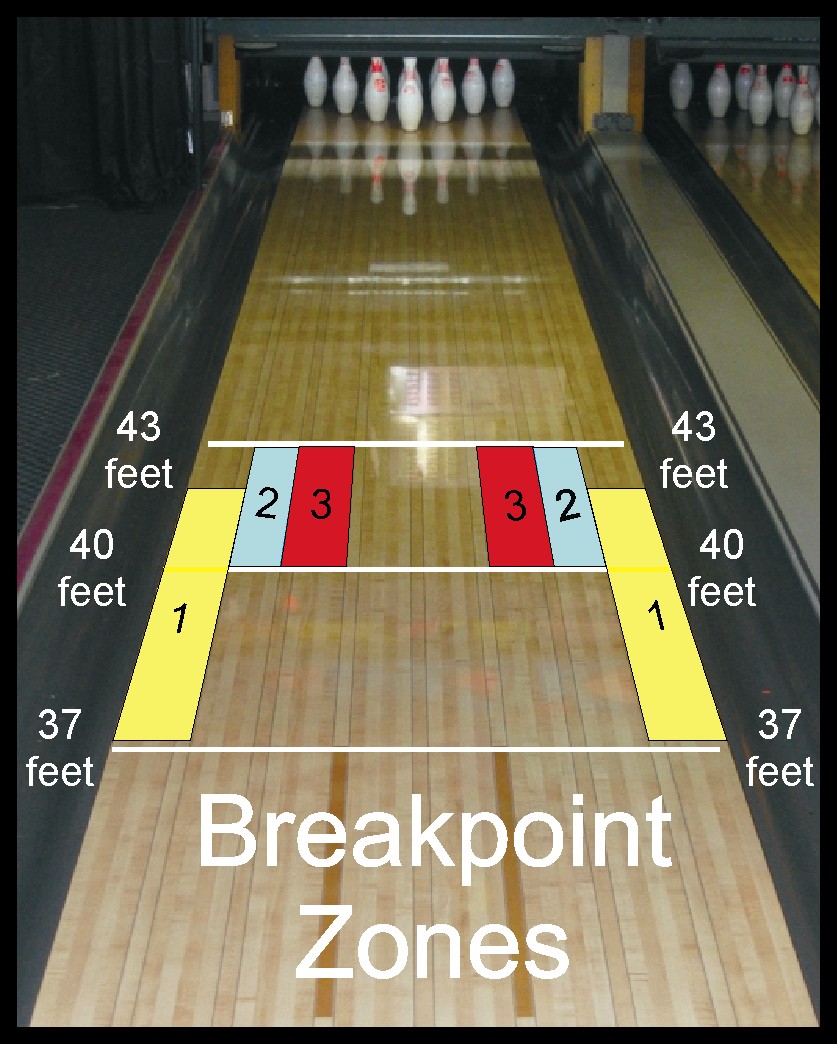

The article also explained that I divide the lane into three “breakpoint zones”. Zone #1 consists of boards 1-5, Zone #2 consists of boards 6-9 and Zone #3 consists of boards 10-14. The object is to throw the ball into the breakpoint zone that will produce the most strikes.

In this article I want to give you some basic guidelines on when to use each breakpoint zone. Choosing and using the right breakpoint zone is one of the most important “top techniques” that I could ever share with you. The sport of bowling at the highest levels of competition has become very complicated due to modern lane oil, high-tech bowling balls, and lane surfaces. The battle on Tour each week is one of “wits”, not physical ability as some people may think. The majority of the players on the PBA exempt list have physical games that are good enough to make TV each week, but we tend to see about 10 players over and over again, with one of the lower ranked players making it now and then.

The top 10 players are winning the battle of “wits” and not the battle of the physical game. I have seen a lot of players at the professional level making adjustments or changing balls thinking that the lanes have changed and that they are simply spraying the ball outside of their usable breakpoint zone. Many times on flatter oil patterns, you only have two boards at the breakpoint, so if you miss by three or four boards, you don’t strike. Unless a bowler is really paying attention, he or she will never even notice a three board miss. The breakpoint zones I am defining below may be four or five boards wide, but that does not always mean you get to use all the boards. As I stated above, on some lane conditions there may be only two boards worth of area at the breakpoint and on other conditions you may have seven.

Defining the zones I will now take a close look at each breakpoint zone, point out when to use them, and a few differences between them. All three breakpoint zones are made of the same material as the rest of the lane, but they are quite unique in the way your ball reacts to them. Each breakpoint zone has a “sweet” board that you should aim for and I will identify each one below. In some cases, the “sweet” board will simply produce the most strikes; in other cases the “sweet” board is more for aiming purposes.

PHOTO #1

Zone #1: Boards 1-5 Oil patterns 38 feet or less The “sweet” board in zone #1 is the one-board; we don’t usually have to actually hit the one-board, just come close. I have found that aiming at the one-board will make most bowlers more successful at hitting breakpoint zone #1. If bowlers aim more inward than the one-board, they are more likely to miss the target zone to the inside. Zone #1 requires a lot of skill to hit consistently, especially from deep inside, so it must be practiced a lot during each practice session. If you don’t practice hitting zone #1 you will never have the skill or guts to use it when there is fame or fortune on the line.

This zone is very different from the other two zones for three reasons. First, it is right next to the gutter and that makes a lot of people very nervous. After all, if you actually did throw the ball in the gutter, it would be the end of the universe as we know it. Honestly gang, if you play breakpoint zone #1, you will throw the ball in the gutter now and then. Just get over it; the rewards you gain by mastering play of zone #1 far outweigh the occasional gutter ball.

Second, you must learn to hit breakpoint zone #1 at different lengths down the lane. This is represented graphically in photo 1; notice how long zone #1 is compared to the other two zones. As a general rule, the shorter the oil pattern, the closer you want to move your breakpoint to the foul line. If the oil pattern is 38 feet, you want the ball to hit the one-board at 39 or 40 feet. If the oil pattern is 35 feet, then you want the ball to hit the one-board around 37 feet down the lane. The reason we pull the breakpoint back toward the foul line as the oil pattern gets shorter is because we need the extra feet of dry backend to use up some of the ball’s energy so it will not overhook.

Third, the first board rarely gets oiled by modern oiling machines, so it can act as a little bumper to keep you from throwing the afore mentioned “universe altering” gutter ball. Don’t be afraid to literally throw the ball “at” the gutter when you see that you have a lot of friction there. It is pretty common to see bowlers throw the ball into breakpoint zone #1, using a target line nearly parallel to the gutter, but many times it would be better to throw the ball “at” the gutter from a slightly deeper target in the heads.

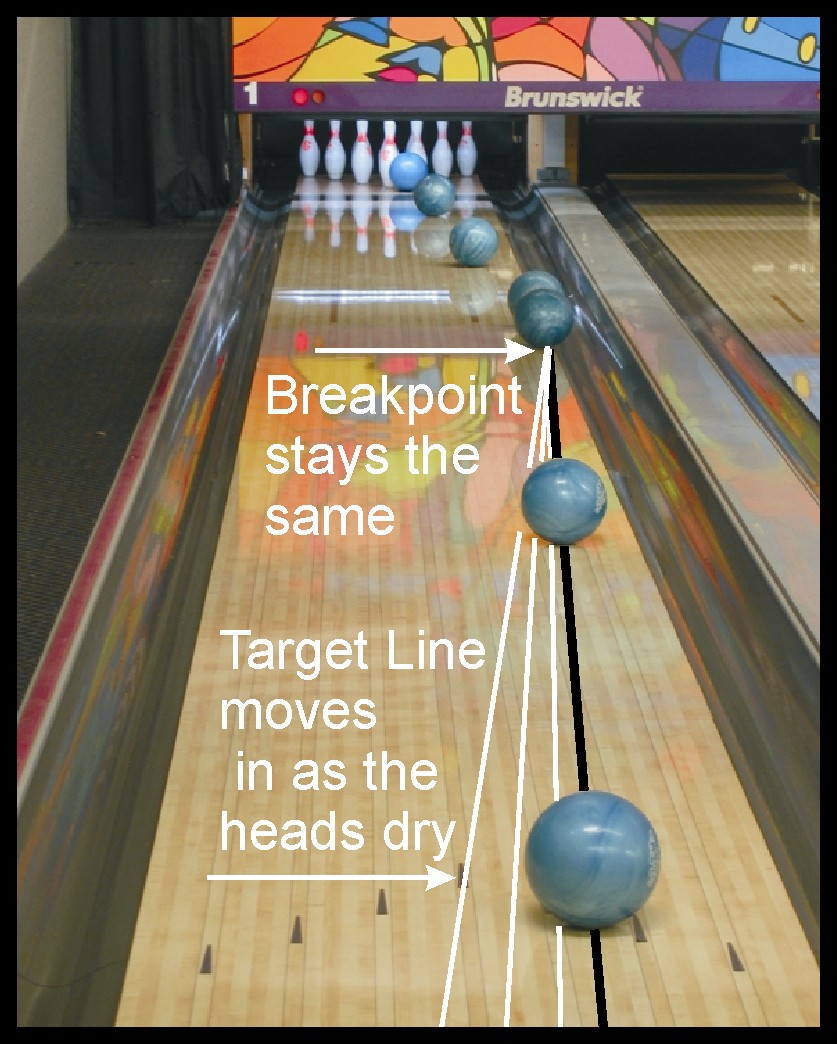

In Photo #2 I have set up a sample shot where a ball crosses the 13-board at the arrows and goes straight to the one-board at a pretty steep angle. The ball reaches the one-board at about 38 feet then goes dead straight (parallel to the gutter) for a foot or two before turning toward the pocket. That section where the ball travels parallel to the gutter is where a war of forces is taking place. The laws of inertia say the ball should continue in a straight line into the gutter, but the axis rotational energy combined with friction with the lane says the ball should turn left. All the battling forces fight to a dead even draw until the friction and rotational forces win over and the ball starts to turn left.

PHOTO #2

When there is a lot of friction on the gutter, throwing the ball there at a steep angle accomplishes three things: 1. The ball uses up a lot of axis rotational energy. That is a fancy way of saying the ball uses up a lot of its energy making the transition from heading toward the gutter to heading toward the pocket. This keeps the ball from overhooking and since the ball is coming at the pocket from such a wide angle, the carry percentage is usually excellent, even if the ball has used up a little too much energy. 2. Creates area that was not a gift from the lane man. Since you are throwing the ball “away” from the pocket, a shot that misses a little inside can still strike. If you were throwing the ball more parallel to the gutter, a miss to the inside is much more likely to cause the ball to go high. This is because of the battle of forces I mentioned above. Since there is little or no inertia trying to take the ball into the gutter, the forces of axis rotation and friction win the battle easily which means the ball will easily hook too much and go high. 3. Creates area (room for error) due to the burn rate of the ball. A miss to the inside that would usually go through the nose and cause a split, will turn into a high pocket strike because the ball has burned up most of its axis rotational energy before it reaches the head pin and stops hooking.

You will occasionally find the one-board too slick to bounce off of, even though it never gets oiled. Balls do transfer oil to the one-board between oiling/stripping sessions, so if the lane machine is not stripping the one-board properly, there will be enough oil residue left on the board to cause your ball to slip off into the gutter. If there is no friction on the one-board then you can’t throw at it from a steep angle.

Photo #2 also shows how the target line moves in (white lines) as the heads dry, but the breakpoint stays the same. Keep in mind that as the target line moves in, the bowler must be able to produce the rev rate needed to bring the ball back; you must stay within your ability. The same inward movement of the target line holds true for the other two breakpoint zones as well. Unless so much oil is depleted that you are forced to move the breakpoint in, you will keep the same breakpoint and just move your target in the heads.

Zone #2: Boards 6-9 Zone #2 is the most used zone of the three; so much so that most bowlers use it without even knowing it. Zone #2 produces the most strikes on a lot of league shots and requires the least amount of skill to hit. Zone #2 is usually used when the oil pattern is between 38 and 41 feet, which covers the vast majority of oil patterns used in every form of competition. The “sweet” board in zone #2 is the seven-board; it is not only the board we aim at, but the one that seems to produce the most strikes. Unlike zone #1, we don’t usually need to worry about how far down the lane we place our breakpoint target. The amount of friction on the lane will determine how far down the ball goes, so just target around 40 feet down the lane.

The biggest mistake bowlers make when playing zone #2 is not watching close enough to notice when the ball slips into zone #3 territory, especially on house shots where there is a lot of oil in the middle of the lane. If boards seven through nine are striking for you and you suddenly hit boards 10 or 11, you will start leaving corner pins. I covered this in detail in the “Breakpoints and Target Lines” article so I will not rehash it here.

Zone #3: Boards 10-14 Zone #3 is the least used of the three breakpoint zones, but nonetheless important when the lane condition calls for it. Zone #3 is generally used on longer oil patterns of 42 to 50 feet. Long oil patterns are in my opinion the hardest to play, so thank goodness we don’t see them too often. Zone #3 places the breakpoint closest to the head pin which is the reason it is used on the longer oil patterns. If the oil man laid down a pattern 43 feet long, the ball is not likely to start gripping the lane until at least 45 feet. That only leaves 15 feet of real estate for the ball to make its turn over to the pocket. If the ball starts that journey from breakpoint zone #1 or #2, it will ether make it to the pocket late, come in behind the head pin, or miss the pocket altogether.

There are a few other times when breakpoint zone #3 should be used even if the oil pattern is not longer than 41 feet:

PBA Player of the Year Tommy Jones won the 2006 US Open playing just this way. Tommy’s ball hit board 11 at the breakpoint just about every time he threw it. This was the case whether he was standing in front of the ball return taking three steps on the right lane or standing at the back of the approach taking five steps on the left lane. As the heads dried, Tommy kept moving his target line left but still nailed the same breakpoint board. All the other bowlers that made the TV show, with the exception of Ryan Shafer, sprayed the ball more at the breakpoint.

Zone #3 has a less defined “sweet” board than the other two breakpoint zones. Sometimes the “sweet” board is number 12, but many times I have seen board 10 work best. When the 10-board is working best, then breakpoint zone #3 will share board nine with zone #2. This means that you may be able to hit board nine at the breakpoint and still strike, but when the “sweet” board is 12, the nine board may not strike.

Believe your eyes not the oil chart |